Analysis of Japanese University Students Communication Skills In In-Person and Online Classes

Research Article - (2022) Volume 7, Issue 1

Abstract

This study examined Japanese university students’ communication skills in English language classes depending on the class modality in-person and online classes. A quantitative survey was used and the Encode, Decode, Control, and Regulate (ENDCOREs) Model scale was employed to measure communication skills. The results showed that several significantly higher scores were found in the online class but for the “Other acceptance,” subscale, the differences in scores between the in-person and online classes were not significant. Moreover, the online class showed higher scores in the communication skills measurements than the in-person class, aside from “Assertiveness” and “Other acceptance.”

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created significant challenges for higher education on a global scale. According to UNICEF (2020), there are more than 1.5 billion students in 190 countries who have not attended school physically. Educational institutions have faced rapid transitions from traditional face to face learning to online learning in a short period of time. Focusing specifically on English as a second language learning (ESL), some research has studied courses in online learning environments (Syahrin, and Salih, 2020).

As part of the pandemic precautions of minimizing transmission of the virus, Office for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control in Japan requested the suspension for classes for elementary school, junior high school, high school and special needs school for a month starting March 2nd, 2020. Responding to the instructions of the Office for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control, the majority of higher learning institutions in Japan rapidly transitioned from the face to face classroom to online learning systems without exceptions.

Literature review

There have been a growing number of studies focused on the outcomes of online learning, especially after the worldwide spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies have reported no significant differences between the online and traditional classroom contexts (summers, Waigandt, and Whittaker, 2005; Mishra, Gupta and Shree, 2020; Wei, and Chang, 2020). In contrast, other studies have reported that online learning is more effective than face to face learning. Rodrigues and Vethamani (2015) point out that the use of computer mediated activity is undeniably helpful in making the learning process more effective and meaningful among ESL learners. In a study by Minh (2021), seven main elements for effective online English teaching are identified: teaching method, course content, learning activities (updated news delivery, games, polls, and student presentations are favorable), myriad interactions (short questions are preferable), learning incentives (e.g., bonus marks), supportive learning environment (teacher voice, praise, encouragement, good teacher student and student student relationships), and supplementary materials (revision, extra resources, etc.). However, most of the research on online learning has been conducted on learning outcomes in English as Foreign Language (EFL) settings. There have been few examinations focusing on the students’ communication skills.

Thus far, various investigations have contributed to the overall development of the research on online learning, especially during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, studies on the communication skills of EFL students in online learning settings have not received much attention. Therefore, this study aims to examine the communication skills of students in online learning settings, including the differences due to the class modalities in English language classes.

The more specific purposes of the present study are as follows:

1. To investigate the students’ communication skills in online English learning settings and face to face learning settings.

2. To examine if there are significant differences in the students’ communication skills between the two learning groups.

3. To clarify the relationship of the differences between each group.

Methodology

The study was conducted at a private university in Tokyo, Japan. The participants were freshmen who were taking English language classes. The questionnaire was distributed in the last class of the semester. The students were informed of the purpose of the questionnaire and were asked to participate in the survey voluntarily.

Explanation of ENDCOREs

The The Encode, Decode, Control, and Regulate (ENDCOREs) Model was used to measure communication skills. It is one of the communication models developed in 2007 by the Japanese researcher Manabu Fujimoto, which was re-modeled in 2013. The ENDCOREs model is well known and is used in Japanese communication studies, especially in the psychology and educational fields. This model is included as one of the major Japanese scales in reference books for psychological measurement. The ENDCOREs scale consists of 24 questions and is divided into six subscales: Expressivity, Assertiveness, Decipherer Ability, Other Acceptance, Self-control, and Regulation of Interpersonal Relationships. Each subscale measures a different communication skill. This scale was chosen for this study because it can systematically grasp multifaceted communication skills. It is also well known to be a feasible scale for comparing different cultures and societies (Naitoh, 2020).

Procedures and Instruments

The participants were asked to rate the questionnaire items using a 7-point Likert-scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: somewhat disagree, 4: Neither agree nor disagree, 5: somewhat agree, 6: agree, 7: strongly agree). The items of the questionnaire are provided in the Appendix

It is noteworthy that most universities have decided to do full online classes in Tokyo, Japan beginning April 2020. Some universities who do not have learning management systems had to use free web services, such as Google classroom, Zoom, and YouTube. However, all the participants were using their university’s learning management system and Zoom.

Data collection and analysis

The data was collected through an online questionnaire to reach as many participants as possible without having to contact them in person. Despite considering both advantages and disadvantages of an online questionnaire, the present study still decided to use an online survey because it seemed to be most feasible to reach a larger sample, especially in the spring of 2020.

The data collection took place in the spring semester in 2019 and 2020. The first questionnaire was conducted at the end of the spring semester in July 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were still face to face classes held. The second questionnaire was conducted at the end of the full online class semester in July 2020 in the middle of the lockdowns. For the first year, the number of valid respondents was 80 students out of 86. There were 89 valid respondents out of 93 students for the second year. It should be noted that of the valid respondents for the second year, 83% (74 students out of 89) were taking a fully online class for the first time.

All the data was collected anonymously and sorted using a spreadsheet. The Statistic Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 28 was used for the data analysis. To examine if there are significant differences in the students’ communication skills between the in-person language classes and full online language classes, a non-parametric t-test was employed. The procedure of the analysis is as follows. First, the validity of the respondents was checked, and descriptive statistics were used to measure the frequency of responses. At this point, it was double checked whether the number of factors is the same as the original ENDCOREs. Six factors were found and the validity of the test was proven. Second, an independent t-test was applied to clarify the differences between the two groups (in-person and full online language classes). Third, to examine the relation difference of each group, the correlation coefficient by class modality was calculated.

Results and Discussion

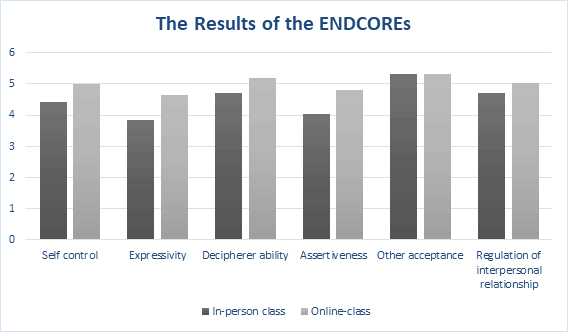

As theThe present study first examines whether there is a significant difference in the students’ communication skills depending on the class modality (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Types of communication skills the students had after their English language class.

Figure 1 shows the results of ENDCOREs in both in person and online classes, representing the types of communication skills students had after their English language classes. As can be seen in Figure 1, the online class group had higher means in most categories except “Other acceptance.” More details for the results of ENDCOREs are shown in (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of the ENDCOREs for In-person Class and Online-Class.

| Types of class modality | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self control | In-person class | 4.43 | 1.15 |

| Online-class | 5.01 | .93 | |

| Expressivity | In-person class | 3.85 | 1.44 |

| Online-class | 4.66 | 1.2 | |

| Decipherer ability | In-person class | 4.71 | 1.33 |

| Online-class | 5.20 | 1.08 | |

| Assertiveness | In-person class | 4.04 | 1.29 |

| Online-class | 4.82 | 1.19 | |

| Other acceptance | In-person class | 5.33 | 1.19 |

| Online-class | 5.33 | .98 | |

| Regulation of interpersonal relationship | In-person class | 4.71 | 1.24 |

| Online-class | 5.04 | .91 |

To test whether the differences found in the responses from the two groups were statistically significant, an independent t-test was performed. The results of the independent t-test are presented in (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of the Independent t-tests.

| In-person class | Online-Class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t-value | |

| Self control | 4.43 | 1.15 | 5.01 | .93 | -3.59*** |

| Expressivity | 3.85 | 1.44 | 4.66 | 1.2 | -3.96*** |

| Decipherer ability | 4.71 | 1.33 | 5.20 | 1.08 | -2.6** |

| Assertiveness | 4.04 | 1.29 | 4.82 | 1.19 | -4.08*** |

| Other acceptance | 5.33 | 1.19 | 5.33 | .98 | -.03 |

| Regulation of interpersonal relationship | 4.71 | 1.24 | 5.04 | .91 | -1.97* |

| * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 | |||||

As shown by Table 2, the online class showed significantly higher scores in Self-control (t=3.59, df=167, p<.001), Expressivity (t=3.96, df=167, p<.001), Decipherer ability (t=2.6, df=167, p<.01), Assertiveness (t=4.08, df=167, p<.001), and Regulation of interpersonal relationship (t=1.97, df=167, p<.05). For “Other acceptance,” the difference in scores between the in-person class and online class was not significant (t=.03, df=167, n.s.)

The results shown in Table 3 and 4 indicate the correlation coefficient between ENDCOREs subscales by class modality. For the in-person class, all the six subscales showed a positive correlation. In contrast, for the online class, “Assertiveness” and “Other acceptance” showed no significant correlation (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Results of the correlation coefficient by class modality for the in-person class.

| Self-control | Expressivity | Decipherer ability | Assertiveness | Other acceptance | Regulation of interpersonal relationship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-control | ― | .44** | .57** | .41** | .45** | .54** |

| Expressivity | ― | .52** | .74** | .4** | .37** | |

| Decipherer ability | ― | .51** | .61** | .62** | ||

| Assertiveness | ― | .3** | .4** | |||

| Other acceptance | ― | .71** | ||||

| Regulation of interpersonal relationship | ― | |||||

| **p<.01 | ||||||

| a. class modality=in-person class; N = 80 | ||||||

Table 4. Results of the correlation coefficient by class modality for the online class.

| Self-control | Expressivity | Decipherer ability | Assertiveness | Other acceptance | Regulation of interpersonal relationship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-control | ― | .22* | .44** | .26* | .41** | .44** |

| Expressivity | ― | .45** | .63** | .25* | .52** | |

| Decipherer ability | ― | .46** | .25* | .53** | ||

| Assertiveness | ― | .053 | .46* | |||

| Other acceptance | ― | .63** | ||||

| Regulation of interpersonal relationship | ― | |||||

| *p<.05, **p<.01 | ||||||

| a. class modality=online class; N=89 | ||||||

This study aimed to clarify students’ communication skills in English language classes depending on the class modality in-person and online learning settings. The results demonstrated that students who took the online class tended to get higher scores on the communication skill scale except for the “Other acceptance” subscale. It is worth noting that the score of the mean for “Other acceptance” is the same, both in in-person and online classes. It can be presumed that students had no difficulty communicating when accepting other students’ ideas or opinions. Moreover, this data implies that communication skills, especially for accepting other students, are irrelevant to the class modality in English language learning. Students may not have the greatest confidence in their English since it is not their first language, so they accept others in both class environments.

Several significantly higher scores were found in the online class than in the in-person class. However, it was only for the “Other acceptance” subscale that the difference in scores between the in-person and online classes was not significant. For the in-person class, “Self-control” showed a positive correlation with “Expressivity,” “Decipherer ability,” “Assertiveness,” “Other acceptance,” and “Regulation of interpersonal relationship.” On the contrary, “Assertiveness” and “Other acceptance” showed no significant correlation for the online class. Considering these results and the result of the differences in score between the in-person and online classes as mentioned, the students who took online classes exhibited more communication skills than those taking in-person classes, regardless of “Assertiveness” and “Other acceptance” skills.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was 1) to investigate the students’ communication skills in online English learning as well as in face-to-face learning, 2) to examine if there are significant differences in the students’ communication skills between the two groups, and 3) to clarify the relationships of the differences between each group.

The following were the main findings: (a) students who took the online class tended to get a higher score on the communication skills scale than the in-person class, (b) both in-person and online classes got the same mean score for “Other acceptance,” (c) several significantly higher scores were found in the online-class but for “Other acceptance,” the difference in the scores between the in-person and online classes was not significant, and (d) “Assertiveness” and “Other acceptance” showed no significant correlation for the online class. Although a single case study cannot provide the communication skill differences according to the class modality, this study suggests the possibility for future English classes. The use of online classes can be an effective approach to communicative English learning. Several limitations arose when designing and conducting this survey. For the online class, the students were not sure when the class would return to the regular, in-person class during the semester because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the class was not designed to be provided as an online class at the beginning of the semester. Further comparative analysis of class modalities should be conducted. Having information about the ESL students’ communication skills in both online and in-person learning settings will help design and deliver the ESL course effectively. This, in turn, helps us to achieve the learning objectives as well as contribute towards positive online an in-person classroom experience.

References

- Fujimoto, M., & Daibo, I. (2007). ENDCORE: A hierarchical Structure Theory of Communication Skills. Japanese J Personal, 15(3), 347-361.

- Fujimoto, M. (2013). An Empirical and Conceptual Examination of the ENDCORE Model for Practical Work with Communication Skills. Japanese J Personal, 22(2), 156-167.

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree A. (2020). Online teaching- learning in higher education during lockdown COVID- 19 pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open, 1.

- Rodrigues, D. P., & Vethamani, E. M. (2015). The Impact of Online Learning in the Development of Speaking Skills. J Interdiscip Res Educ, 5(1), 43-67.

- Summers, J. J., Waigandt. A, & Whittaker, A. T. (2005). A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus a Traditional Face-to-Face Statistics Class.Innov High Educ, 29(3), 233-250.

- Syahrin, S, & Salih A. A. (2020). An ESL Online Classroom Experience in Oman during Covid-19. Arab World Engl J, 11(3), 42-55.

- A hierarchical Structure Theory of Communication Skills. Japanese J Personal

- Wei, Z, & Chang Z. (2020). Blended Learning as a Good Practice in ESL Courses Compared to F2F Learning and Online Learning. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 12(1), 64-81.

Author Info

Haruka Fujishiro*Received: 02-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. jflet-21-50210; Accepted: 23-Feb-2022, Pre QC No. jflet-21-50210(PQ); Editor assigned: 04-Feb-2022, Pre QC No. jflet-21-50210(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Feb-2022, QC No. jflet-21-50210; Revised: 23-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. jflet-21-50210(R); Published: 02-Mar-2022

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.